Walking the Story

Walking the Story

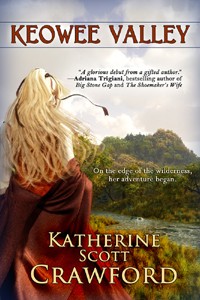

By the time my debut historical novel, Keowee Valley, was published, I’d walked, hiked, trail run, swum, paddled, and climbed countless miles of rocks, roads, flatland and mountain trails, lakes and rivers in the foothills and mountains of Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Tennessee. Some of this, I’d done as a child, because my family were outdoorsy types. Most, however, I’d done on my own: both as a camp counselor and backpacking guide in my teens and 20s, and on adventures with like-minded friends well into my 30s, the age I am now. Always, and until her death in 2015, I was joined by my faithful trail partner: my dog, Scout.

I go (and went) to the woods—and the forest, the lake, the mountaintop, the river—to “live deliberately,” much the same as Thoreau did in the mid-1800s (minus the wood-chopping). The “woods” bring me back to myself; there is no place I feel more authentic.

The heart of my historical novel, Keowee Valley, takes place in the woods—in the forests of the Southern Appalachians. In fact, nearly every scene in the wilderness sections of the novel occur in real spots: scenery in which I’ve hiked, rivers I’ve paddled (and fallen into), trails I’ve traversed, in all kinds of weather. It is a land I know intimately. I know it as well as the pages of my own heart.

Every time I write a story, place—or setting, as some like to call it—plays a vital role, as important as any character. Maybe it’s the Southern writer in me? Southern writers are such, of course, because of their place. Mostly, I think, it’s because I can’t separate from the land, and neither can my characters. After all, in Keowee Valley, Quinn falls head over heels in love with the dangerous, gorgeous, and wild Cherokee backcountry long before she ever lays eyes on the equally dangerous (and gorgeous, and wild) Jack Wolf.

Bio:

Katherine Scott Crawford is a novelist, newspaper columnist, college English teacher, hiker and mom who lives in the mountains of Western North Carolina. Her parenting and outdoor life column appears weekly in The Greenville News (South Carolina), and is often picked up by other newspapers across the country. She holds far too many degrees in English and writing, chases her children frequently through the Pisgah National Forest, and is currently at work (when she’s actually sitting down) on her next historical novel.

Pick up Keowee Valley by Katherine Scott Crawford today for  just $1.99!

just $1.99!

“A glorious debut from a gifted author.” – Adriana Trigiani, bestselling author of Big Stone Gap and The Shoemaker’s Wife

“Keowee Valley is a terrific first novel by Katherine Scott Crawford–a name that should be remembered. She has a lovely prose style, a great sense of both humor and history, and she tells about a time in South Carolina that I never even imagined.” –Pat Conroy, bestselling author of The Prince of Tides and South of Broad.

On the edge of the wilderness, her adventure began.

She journeyed into the wilderness to find a kidnapped relative. She stayed to build a new life filled with adventure, danger, and passion.

Spring, 1768. The Southern frontier is a treacherous wilderness inhabited by the powerful Cherokee people. In Charlestown, South Carolina, twenty-five-year-old Quincy MacFadden receives news from beyond the grave: her cousin, a man she’d believed long dead, is alive–held captive by the Shawnee Indians. Unmarried, bookish, and plagued by visions of the future, Quinn is a woman out of place . . . and this is the opportunity for which she’s been longing.

Determined to save two lives, her cousin’s and her own, Quinn travels the rugged Cherokee Path into the South Carolina Blue Ridge. But in order to rescue her cousin, Quinn must trust an enigmatic half-Cherokee tracker whose loyalties may lie elsewhere. As translator to the British army, Jack Wolf walks a perilous line between a King he hates and a homeland he loves.

When Jack is ordered to negotiate for Indian loyalty in the Revolution to come, the pair must decide: obey the Crown, or commit treason . . .

From Jeanne Stein

From Jeanne Stein

When I was three, the head of the children’s department in the Belk-Harry department store gave me a little red piano, a prop from one of the display cases—because she could see I loved it, and she was that kind of person. When I was twenty-three and a night nurse, I was taking care of a violent stroke patient, a woman no one else wanted to take care of. I saw a man standing just outside the doorway. I asked if he was family. He said no, but he’d known her a long time, and he could hardly bear to see her like that. She was, he said, the head of the children’s department at Belk-Harry’s for many years, and she was one of the kindest women he’d ever known. Me, too, I suddenly realized.

When I was three, the head of the children’s department in the Belk-Harry department store gave me a little red piano, a prop from one of the display cases—because she could see I loved it, and she was that kind of person. When I was twenty-three and a night nurse, I was taking care of a violent stroke patient, a woman no one else wanted to take care of. I saw a man standing just outside the doorway. I asked if he was family. He said no, but he’d known her a long time, and he could hardly bear to see her like that. She was, he said, the head of the children’s department at Belk-Harry’s for many years, and she was one of the kindest women he’d ever known. Me, too, I suddenly realized.